The following is part of a series of articles written in honor of eighteen African American men from Tippecanoe County who served their country during World War I. Initial information was extracted from the Tippecanoe County Honor Roll Book published in 1919. The lives of these men were researched by the General de Lafayette Chapter Black History Committee and preserved in written form. The project received national recognition from the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution in 2020. Thank you to Renee’ Thomas (Purdue Black Cultural Center) and Sana Booker (West Lafayette City Clerk) for serving as advisors for the project.

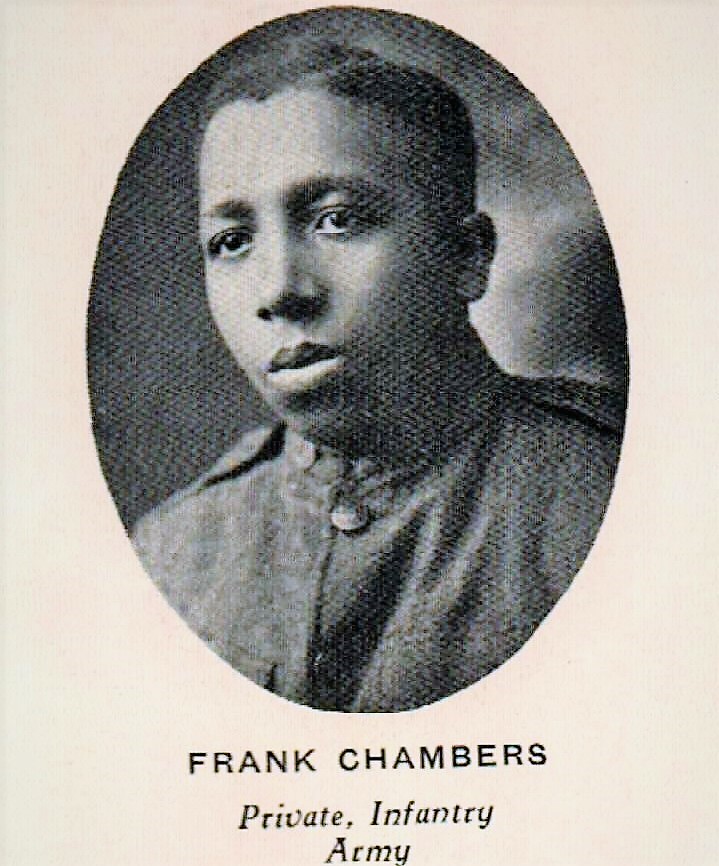

Frank Chambers (1897-1954)

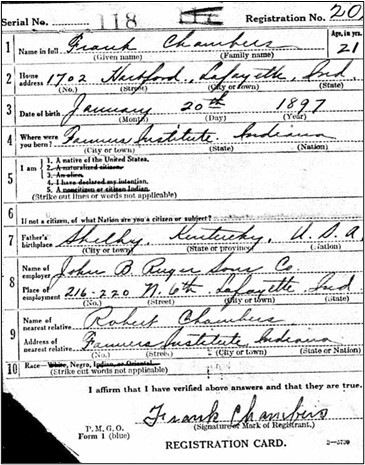

The history of the Chambers family in Tippecanoe County is a bit out of the ordinary for African Americans during the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era. Frank Chambers, the subject of this biography, and his siblings were raised in a quiet Quaker community known as Farmers Institute in southwestern Tippecanoe County near Shadeland, Indiana. Frank was born on January 27, 1897, to Robert and Mollie (Clay) Chambers in a farmhouse owned by Buddell and Elizabeth “Betsy” Sleeper.

Buddell and Betsy Sleeper, who were Quaker, were both conductors and stationmasters on the Underground Railroad. They transported and provided a safe-haven in their home for traveling freedom-seekers.

How the Chambers family came to live in an all-white religious community has been the subject of speculation throughout the years. One might conclude that it was due to the friendly atmosphere that existed between Quakers and the African American community. What caused them to leave their home in Kentucky is another story.

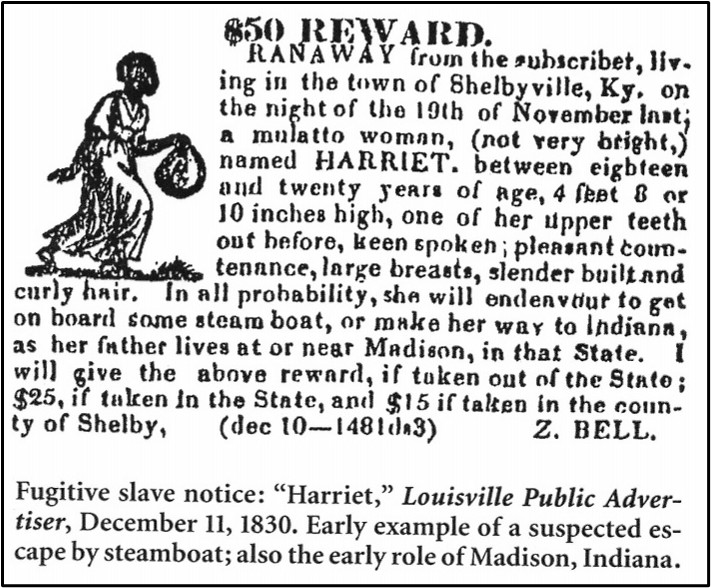

A Thriving Slave Trade

The Chambers’ new home in Indiana was a stark contrast to the atmosphere in Shelbyville, Kentucky where there were active slave markets prior to the Civil War. A significant number of slaves were traded or purchased among Shelby County slave owners. One of the most notorious slave traders, Pierce Griffiths, lived in Shelby County, Kentucky. In 1800 there were about 40,000 slaves in Kentucky, and by 1820 there were a staggering 126,733 slaves in the state. According to historical accounts, Shelby County’s slave population grew from 36% to 41% from 1840 to 1860. Prior to moving to Indiana, the Chambers family lived within the confines of this horrific reality.

Black folks living in Shelby County could not even count on their pro-Union neighbors for support since many Kentucky Unionists did not object to slavery. Some of them even resented the formation of the “U.S. Colored Troops.” Due to the hostility and oppression that surrounded them, slaves from Shelby County poured into recruitment centers at the announcement of the formation of the United States Negro troops.

Many anti-slavery activists had already fled north years before the start of the Civil War, leaving little hope for slaves in the area. There were, however, several Manumission societies in Kentucky with one active group in Shelby County. Manumissions societies were started by Quakers in North Carolina. These missions eventually spread to Tennessee and Kentucky. The objective was for Quakers to purchase slaves and then set them free. Many of the freed slaves were taken to Indiana by Quakers where they were given opportunities to start new lives among other Quaker families.

It is entirely possible that the Chambers family were helped by Quakers who operated one of the Manumissions in their county. By the time Ann Chambers and her family moved to Indiana, there was no need for Quakers to purchase them as slaves, but the need for safety was a pressing one the emancipated former enslaved. The Quaker network throughout the Midwest was well-established. The fact that the Chambers family settled near the Farmers Institute is a good indication that they were directed there by other Quakers.

Reflections from a Former Black Quaker

In a 1984 interview with Jack Alkire of the Journal and Courier, George Chambers reflected on his life in the Quaker community.

“I have pleasant memories growing up in that neighborhood,” said George, who recalled living and working on farms in the area before moving to Lafayette in 1929. “It was a nice place to grow up whether you were black or white.” George also said that he would drive through the area from time-to-time to reflect on the good times he had growing up there.

Ann Chamber’s dream of a better life for her children and grandchildren had been realized.

A New Beginning for Freedom Seekers

A report entitled, “A History of Farmers Institute Monthly Meeting of Friends and Its Community,” written by Nellie Taylor Raub in 1951, gives a further glimpse into the lives of Frank’s ancestors soon after they arrived in 1868.

“There was only one colored family in the Farmers Institute neighborhood,” wrote Raub. “No one is left to explain why they chose this community when they decided to move north. They did not come by way of the Station of the Underground Railroad for they arrived after the Civil War. They may have come to Farmers Institute because they knew it to be a Quaker stronghold and expected Friendly treatment.”

Ann (Wilson) Chambers, a widow from Shelby County, Kentucky, made her way to the Quaker community in 1868 with her father, George Wilson, and six children: Ben, George, Jr., Frank, Robert, Harriett, and Julia Chambers. The former slaves were free to pursue their dreams and enjoy the fruits of their own labors.

Raub gives a glimpse of those early years on the farm. “Ann was a good, religious, hard-working woman. There are those still living who can remember her singing of Negro Spirituals. Her son, Ben, (a powerfully built man) inherited his mother’s love of music. He was ingenious, too. He wished to play two instruments at the same time. He went to the blacksmith’s shop near his home and bent a small iron rod so that it would rest around his neck and hold a harmonica in front of his lips. In this way, he was enabled to play a tune on the harp and accompany it by strumming on a banjo or guitar, suspended by a strap across his shoulders. The neighbors often heard his sweet music as he played after dark, strolling home from work.”

Ann’s daughter, Harriett, known as “Hattie,” died in 1932 at the age of 81. An October 29, 1932, newspaper obituary notice confirmed that Hattie had been born into slavery. The report stated that she was “one of the few negroes left who was born into slavery.” The report confirmed that “she came to this part of the country soon after the close of the Civil War.”

Bob and Mollie Chambers Raise a Family

Raub’s report also stated that “Ann’s son, Robert, always called ‘Bob’, began work for Jonathan Baugh, at the age of twelve, or thereabouts. He joined the Friends Church, where it seems he should still be sitting in his favorite place—a seat near a window on the men’s side (west). He was married to Mollie Clay in 1884, and four children were born to them: Courtney, Frank, Lester, and Mayfair,” reported Raub.

Bob didn’t just work the farm, he eventually managed it. Frank and Courtney helped work the farm during their teenage years. It was a sad day for the family on April 22, 1916 when Bob and Mollie’s oldest son, Courtney, died of Tuberculosis at the young age of 21. Courtney was laid to rest in the cemetery at Farmers Institute.

Mollie Chambers became ill during the summer of 1928. She spent ten days at St. Elizabeth Hospital prior to her death on July 30, 1928. The cause of death was listed as rheumatism of the heart. She was buried at the Farmers Institute cemetery.

After Mollie’s death, Bob retired from farming; however, he continued to live in the Quaker community. Census records from 1930 indicate that he was employed by Henry and Elizabeth Anderson as a house servant in Union Township near the Farmers Institute where he worshipped as a member of the church. “He spent the last three years of his life at the home of his daughter, Mayfair C. Lowell, in Hinsdale, Illinois. He lived to be nearly 100 years old and kept a clear mind to the last, falling peacefully asleep February 18, 1949,” reported Raub.

Frank Chambers Enlists in Army

Young Frank Chambers enlisted in the Army and entered service on September 25, 1918, at Camp Sherman in Ohio where he was met with a large outbreak of the Spanish Flu. Camp Sherman, located near Chillicothe, Ohio, was the third largest training camp in the nation during that time. It also served as a German prisoner of war facility. Frank never saw action since the war ended less than two months after his enlistment. He received an honorable discharge for his short stint in the service.

After the War

Prior to the war, Frank was employed as a houseman at the Fowler Hotel and as a driver for John B. Ruger & Sons. A bakery owner, Mr. Ruger was a prominent citizen of Lafayette. From 1927 until his death in 1954, Frank was employed as a waiter, both in Lafayette and later as a head waiter in Grand Rapids, Michigan where he lived after marrying Beatrice Williams on March 16, 1925. It does not appear the couple had children.

Frank is buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery at Grand Rapids, Michigan in an unmarked grave. It is likely that he did not receive a military headstone because he did not have descendants to make such a request at the time of his death.

The Legacy of Ann Chambers

The legacy of Ann Chambers and her descendants left an indelible mark on society. Well-respected in the Quaker community, Ann’s Christian faith guided her through the trials of life. She taught her children the value of hard work. She taught them that love transcends race. Ann accomplished the mission of providing a better life for her children and grandchildren. Born into slavery, she understood the value of freedom and the price that was paid to receive what was rightfully hers. The legacy of Ann Chambers is worth remembering.

A descendant of Ann Chambers was located recently and honored by the Chapter at the 2021 Juneteenth Celebration in West Lafayette, Indiana. Sharon Chambers Ford was honored by the chapter at the 2021 Juneteenth Celebration in West Lafayette, Indiana.

DAR Chapter Marks Local UGRR Site

On Saturday, June 2, 2018, the General de Lafayette Chapter marked the site of the Buddell Sleeper House Underground Railroad Station. The project was especially meaningful to chapter historian, Kathryn Windle Cox, since she is a direct descendent of the Sleepers.

Cox published a commemorative program booklet that told the following story about her ancestors:

“Buddell and Betsy, along with their first-born daughter, Martha Ann, moved to Tippecanoe Co. IN from Clark Co. OH in the fall of 1835. They settled in the newly established Quaker settlement that would later become known as Farmers Institute; a community that was sometimes referred to as Quaker Grove.

Patience Burroughs was born near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1767 and married Samuel Sleeper in 1787 in Montgomery County, New York. Patience and Samuel were Buddell Sleeper’s parents. Patience was the first recorded minister at Flint Creek Preparative Meeting, later renamed Farmers Institute Friends Meeting.

This was Buddell and Betsy Sleeper’s house prior to a fire that damaged but didn’t destroy the house. Some features from the original house can still be found in the house that run-away freedom-seekers saw as a safe place in this strong Quaker community.”

Union Township District School #5

The school was located next door, across a small stream, to the west of the original Farmers Institute Academy. This was a two-room, one-story public schoolhouse. Opening around 1874, after the close of the Farmers Institute Academy, this school offered eight grades of common school subjects and continued until 1911 when it was replaced by a consolidated Union Township School that was erected about one mile south of Shadeland.)

The known students are as follows:

2nd Row: third from left-Everett Windle (future husband of Myrtle Whitsel)

Sixth from left-Elizabeth “Lizzie” Windle (future wife of Gurney Chappell) – Everett and Lizzie were children of Isaac and Mary E. Sleeper Windle.

3rd Row: fifth from left – Kate Baugh (future wife of John Hayes Bone)

Sixth from left-Bessie Osborn (Bessie was the daughter of Job and Hannah C. Sleeper Osborn)

***Three grandchildren of Buddell and Elizabeth Welch Sleeper, Underground Railroad Conductors and Stationmasters, are in this group: Bessie Osborn, Everett Windle, and Elizabeth “Lizzie” Windle.

****The two African-American children most likely are Chambers family members.

Photos courtesy of Kathryn Windle Cox, a Sleeper descendant

About the Black Yankees Project

This is part of a compilation of research conducted by the Black History Committee of the General de Lafayette Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution, in commemoration of the official end of World War I on November 11, 1918. It is the goal of the committee to preserve the memories of the African American men from Tippecanoe County who served with honor and distinction in the Great War.

Initial information was extracted from the Tippecanoe County Honor Roll Book, published in 1919. Additional records, including census, marriage, death, military, news clippings, and other historical information were used to create the following biographical sketches for the men.

By November 11, 1918, over 350,000 African Americans had served on the Western Front. Eighteen of those men were from Tippecanoe County. These Great War veterans from Tippecanoe County are deserving of special recognition, especially since they were not given proper credit or treatment for the many sacrifices they made on behalf of the nation. Regrettably, the biographical photographs of our county’s African American soldiers were placed on the last pages of the biographical section in Tippecanoe County’s World War I Honor Roll Book.

In addition, biographical data for these brave soldiers were not forwarded to the Indiana State Library to be placed in the historical files with other local veterans. The General de Lafayette Chapter would like to rectify this oversight. The chapter will provide the Indiana State Library with complete biographical material for each African American World War I veteran.

Editor’s Note:

The title for the booklet was inspired by Thomas Davis, an African American First World War Veteran who shared his experiences at the age of 105 in 1997 with authors Eric and Jane Lawson. Mr. Davis served his tour of duty in France, alongside French soldiers who gave Black Americans more honor and respect than they received from some of their own countrymen.

Davis recalled that the people of France referred to African American soldiers as “Black Yankees.” He didn’t take offense to it as it was meant as a term of endearment. Black soldiers were held in high regard by their French counterparts, as well as French citizens, for the efficient and swift movement of supplies.

“The Negro Service of Supply men acquired a great reputation in the various activities to which they were assigned, especially for efficiency and celerity in unloading ships and supplies of every sort at the base ports. They were a marvel to the French and astonished not a few of the officers of our own army,” wrote the author of the History of the American Negro in the Great War.”

The Daughters of the American Revolution agree that the “Black Yankees” of the Great War were a marvel and emphatically worthy of honor.

Reviews

“Black Yankees masterfully illustrates the role of eighteen African American World War I Tippecanoe County, Indiana soldiers who overcame society’s limitations. Far too long the American story has neglected to mention the role of African American men and their contributions. Thank you to General de Lafayette Daughters of the American Revolution for researching and compiling the inspiring biographies. This publication ensures these soldiers will no longer be subject to erasure.”

-Renee Thomas, Director, Purdue University Black Cultural Center

“The dedication of the African American soldier throughout America’s history has often been overlooked, ignored or simply forgotten. Until now, through the committed efforts of the General de Lafayette, Daughters of the American Revolution, “Black Yankees” tells the stories of eighteen African American World War I Indiana soldiers. The research involved in speaking of their personal histories and their willingness to stand for a country, that more often than not, did not stand for them, is a testament to their grit and that of these amazing women who brought their stories to light. Thank you for your work, and I am eternally grateful to have learned, through you, about these great Americans.

-Sana G. Booker, West Lafayette City Clerk